FORCING THE VOSGES PASSES A great offensive to drive the Germans west of the Rhine surged forward early in November along the entire Allied line. Within the Seventh Army sector, the XV Corps, on the left of the VI Corps, began operations to penetrate the Saverne Gap, leading to Strasbourg. The First French Army, on the right of VI Corps, launched an attack through Belfort Gap paralleling the Swiss border. These two relatively open passes had been the traditional highways of invasion for years.

The enemy intended to hold a winter line at the Meurthe River. Elaborate defenses—trenches, tank traps, barbedwire—had been built during the preceding two months by troops, labor units and vast numbers of forced French workmen. On the west side of the river and in front of this defense, all villages and even many single buildings had been burned down so that no shelter would be available to the Allies facing the Meurthe River Line in the coming winter months.

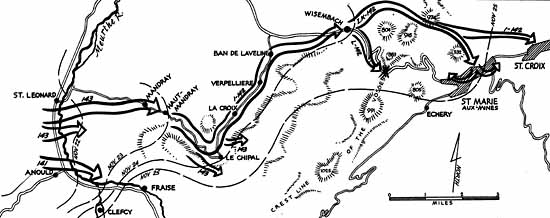

Acting speedily, the 143rd attacked on November 21st encountering high water and stiff resistance. Sensing the developing danger, the Germans started shifting troops to that sector. Aided by their fortifications, they were able to confine progress to a narrow area between the river and the hills. Next clay all three battalions of the 143rd resumed the attack and were assisted by the 1st and 3rd Battalions, 141st, who changed direction and crossed the river on the right flank of the 143rd. This added weight broke the defense, it becoming apparent early on November 23rd that the Germans could not hold much longer. The 142nd, which had been pulled out of the line on the 20th, was alerted and told to be ready for a breakthrough. Late in the afternoon the 1st Battalion, 142nd, under Lt. Col. James L. Minor, mounted on tanks, tank destroyers and artillery vehicles, started forward. At Haute Mandray the Germans put up a last-ditch stand. Taking up the battle on foot and fighting all night, the battalion forced its way up and over a narrow, precipitous road through the villages of Le Chipal and La Croix-Aux-Mines into the town of Ban-de-Laveline, a march of eleven kilometers. The Division front, winding from a point near Gerardmer to the newly-won Ban-de-Laveline, now stretched more than thirty kilometers.

GERMANS HALT MOVEMENT ON ROAD The Germans that had been defeated at Haute Mandray infiltrated back into the hills and throughout daylight of the 24th succeeded in keeping the road near Le Chipal under fire, preventing further movement of vehicles or troops. The 143rd was employed all day in the tedious job of locating and destroying the enemy machine guns and mortars effecting the temporary blockade, a job extremely difficult because of the rough terrain and heavy woods. However, movement toward St. Marie Pass was not held up until the road could be cleared. The 1st Battalion, 142nd, without waiting for support pushed on and captured Wisembach at the foot of the pass. At nightfall the remainder of the 142nd pushed on into Ban de Laveline. The 143rd was ordered concentrated in La Croix-Aux-Mines and the 141st and the 36th Reconnaissance Troop, to keep contact with the First French Army whose flanking elements were still in the vicinity of Gerardmer, extended their lines to a total of twenty kilometers.

The haze of a frosty late autumn morning hung over St. Marie Pass on November 25. Under cover of the misty atmosphere a small force consisting of Company 1, 142nd Infantry, several tank destroyers from the 636th TD Battalion, and a platoon from Company M, under command of the 3rd Battalion Executive Officer, Major Ross L. Young, moved up the road to the pass. At the same time, the Battalion Commander, Lt. Col. A. Ward Gillette, led the remainder of the 3rd Battalion on a circuitous route several miles to the left (north) of the road over terrain so rugged that no artillery, no armor, and no vehicles could accompany them. The men were armed with only what they could carry in their hands. After four hours of hard climbing they approached St. Marie from the rear. COMPLETE SURPRISE Racing down from the heights, Company K was the first to strike the town. A complete surprise was effected. German soldiers were captured riding bicycles in the streets. Company I entered the town farther east and met only sporadic resistance but at the railway yard and station one hundred Germans tried to make a stand. On the slopes northeast of town another enemy group held off three platoons until midnight. However, resistance was ineffectual because of the surprise. Eighty prisoners and large stores of booty were lifted from a German barracks in the heart of town. By late afternoon, St. Marie was entirely in our possession. One hundred seventy prisoners were taken in the town while the 3rd Battalion suffered only two minor casualties.

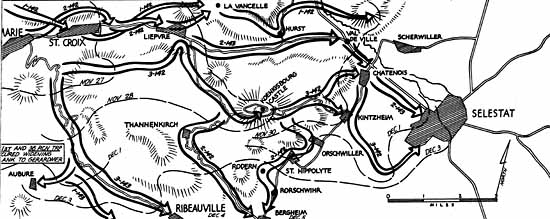

The highest, narrowest, and toughest pass of the Vosges had thus been breached. This was the one the Germans had thought impregnable. In a whining bleat the German communique reported that overwhelming forces had driven back their defenses at St. Marie. Actually they had not been driven back but destroyed, and by a single battalion numbering less than 500 effectives which had consummated one of the riskiest and most brilliant maneuvers of the war. St. Marie had fallen, the crest of the Vosges had been passed, the gateway to the Alsace Plain swung open. Many miles of the narrow mountain pass still remained before the plains of the Rhine Valley would be reached, however. There was no time to pause. Even while the 3rd Battalion was mopping up St. Marie, the 1st Battalion, 142nd, pushed on towards St. Croix, next major objective two miles beyond in the pass. The 1st had followed the 3rd over the mountain heights but continued directly on as the latter turned to attack St. Marie. For some seven kilometers its riflemen, machine-gunners and mortarmen packed their loads over the fantastically difficult mountain terrain. No armor or transport could follow them. Blankets had been discarded in order to carry extra ammunition and the battalion faced the possibility of faring on its own for some time, as, when it started, the issue at St. Marie had not been decided. It was after dark before the hills immediately overlooking St. Croix were reached. The attack was launched early the next morning but the Germans, alerted by the St. Marie incident, had rushed reinforcements up from Selestat, and capture of the town required two days. The 2nd Battalion, 142nd, moving in from the direction of St. Marie, assisted the 1st Battalion coming down from the hills, in the reduction of St. Croix. While the advance through St. Marie Pass was under way, far to the right on the Division’s drawn-out flank, the 141st kept up a steady pressure on German elements in the hills along the Meurthe River. They captured Clefcy, Fraize and Scarupt and pushed toward Bonhomme Pass. The Germans were shelling Clefey and Anould at the same time Division spearheads fought into St. Croix. The 143rd, committed to clearing the ridges east of Ban de Laveline and La Croix, was brought up to St. Marie soon after the town fell, relieving advance elements there and then pushing southeast on the much-blocked road leading to Ribeauville. ANOTHER SURPRISE WINS

The enemy was now frantic in his efforts to halt the Division advance. He had failed to hold the pass. To the north the Alsace Plain had been entered and Strasbourg taken. To the south the French had come through the Belfort Gap. A sudden debouchment at Selestat would mean ruin for the German forces in the Plain. The enemy therefore tried to hold the exits of the St. Marie Pass while at the same time harrassing the lengthening flank of the 36th. He failed in both efforts. To speed the outlet from the pass the 2nd Battalion, 143rd, was attached to the 142nd Infantry. Continuing to strike the enemy in flank by sending battalions over the steep ridges on foot, Liepvre and the surrounding hills was cleared by dark of the 29th. One German battalion sent in to reinforce the garrison was caught and completely destroyed by the 1st Battalion. While the 2nd Battalion, 142nd, shifted to Koenigsbourg to protect the right flank of the regiment, the 3rd Battalion took Chatenois and Kintzheim in the Rhine lowland. The 1st Battalion, 142nd, at night waded a stream shoulder deep, and, leaving its dead and wounded behind, climbed the last ridge north of the pass overlooking the valley. At the same time the 2nd Battalion, 143rd, drove along the main road and captured Val de Ville at the mouth of the pass. The 36th Division was in the Plain on November 30th. This was the goal. Previous orders from Corps limited any further advance. However, on December 1 General Brooks called the Division Commander and ordered the 36th to move out to capture the southern half of Selestat, the largest city in Alsace between Colmar and Strasbourg. The 103rd Division farther to the north was given the job of taking the northern half. Reconnaissance was started at once and the 2nd Battalion, 143rd, and 3rd Battalion, 142nd, moved into position. Under cover of a heavy fog the attack was launched at four o’clock in the afternoon. Across three miles of open flat vineyards the assault moved forward. By ten at night a foothold had been gained in the western and southern edges of the city and the Selestat-Colmar road cut. All the next day the fight for the city continued and by early morning of the 3rd the assigned objective was completely in Division hands. The 103rd, with a longer distance to go, completed their mission on the 4th, when the 36th assumed the defense of the entire city. FIRST TIME IN HISTORY

The 1st Battalion cleared Aubure in sharp fighting and the 3rd Battalion drove on into Ribeauville on December 3. 143rd elements then fanned out in the Rhine lowland and contacted the 142nd at Bergheim where hundreds of the enemy fleeing before the Division advance, were overrun. In the period from November 20 to December 4, in forcing St. Marie Pass, over 2,200 prisoners were taken by the Division. CMH FOR SERGEANT ELLIS A. WEICHT

|

At St. Hippolyte, Sgt. Ellis A.

Weicht’s action won the CMH, posthumously. When the Germans counterattacked,

Sgt. Weicht led his squad in clearing the enemy from several houses. The advance held up

by a German machine gun, Weicht scaled a wall, flanked the position and wiped out the gun

with rifle fire. Farther along the street a 20mm gun opened up. As friendly artillery

concentrated on the target, Weicht remained in a close position to snipe at the crew and

force them to abandon their piece. Later, at a German roadblock, he killed three Germans

and wounded several others while the enemy raked him with machine gun fire. Weicht was

killed when the enemy turned an anti-tank gun upon him.

At St. Hippolyte, Sgt. Ellis A.

Weicht’s action won the CMH, posthumously. When the Germans counterattacked,

Sgt. Weicht led his squad in clearing the enemy from several houses. The advance held up

by a German machine gun, Weicht scaled a wall, flanked the position and wiped out the gun

with rifle fire. Farther along the street a 20mm gun opened up. As friendly artillery

concentrated on the target, Weicht remained in a close position to snipe at the crew and

force them to abandon their piece. Later, at a German roadblock, he killed three Germans

and wounded several others while the enemy raked him with machine gun fire. Weicht was

killed when the enemy turned an anti-tank gun upon him.