We apoligize for any inconvenience and hope you will visit us soon.

We apoligize for any inconvenience and hope you will visit us soon.

Author: Lisa Sharik

Liviing History Weekend and WWII Battle Reenactment

Camp Mabry Living History Weekend

Hosted by the Texas Military Forces Museum

(3038 W 35th St, Austin, Tx 78703)

April 15-16

9 a.m. to 4 p.m.

Take a stroll through Texas Military History at Camp Mabry’s Living History Weekend on Saturday April 15 and Sunday April 16. This free event, hosted by the Texas Military Forces Museum, will allow visitors to see uniforms, equipment, weapons, tents, communications gear, military vehicles and more dating from the earliest days of the Texas Militia and the Texas Revolution through the end of the Cold War. Find out what was life for soldiers during the Texas Revolution, the Mexican War, Civil War and Spanish-American War. Learn about the role of the Texas Rangers as a 19th Century military force defending Texas’ borders. Explore the realities of camp and battlefield for troops in World War I as well as American, German, British and Russian soldiers in World War II, as well as the Vietnam War. Stand alongside dozens of historic military vehicles including jeeps, tanks, halftracks, trucks and weapons carriers. Watch displays of 19th Century weapons and absorb the sound and fury of a full-scale World War II battle reenactment complete with artillery, tanks, machines guns and over 100 reenactors. Tour the 26,000 square-foot Texas Military Forces Museum and its impressive display of artifacts, tanks, helicopters, jets, weapons, uniforms and more. An ideal educational and commemorative experience for the whole family!

The event will take place rain or shine. 19th Century Weapons Demonstration at 11:30 a.m. each day. World War II Battle Reenactment at 1:00 p.m. each day. Bleacher seating, souvenirs and snacks available. Free admission and free parking. Adults must show a valid photo ID to enter Camp Mabry. For more information visit www.texasmilitaryforcesmuseum.org or call 512-782-5659

WWII “Victory” Dinner Dance Gala

It is time again for the annual Texas Military Forces Historical Foundation WWII themed Sweetheart Dinner Dance. The event will take place at the museum on February 11, 2023 starting at 6:30 pm. As always we will feature the talented Sentimental Journey Orchestra under the direction of Ted Connerly and featuring the Memphis Belles singers. Dinner will be provided by Austin Catering, and a photo booth and souvenir glass will add to the vintage atmosphere. This year instead of the traditional silent auction we will have a bazaar which will allow you to take your purchases immediately.

Tickets are $100 and can be purchased at the event page , by phone or at the museum. Seating is limited.

We look forward to having you join us for this wonderful unique event hosted by the Texas Military Forces Historical Foundation which supports the Texas Military Forces Museum.

Internship Program- Spring 2023

Camp Mabry, 2200 W 35th St. Austin, Tx

Short Description

The Texas Military Forces Museum intern will be intimately involved in learning the operations of a large museum with a small staff. The intern will engage in all aspects of museum work including cataloging, collections management, exhibit design and construction, special and educational events, fulfilling research requests, giving guided tours, administrative duties to include non-profit retail management, and operational management of the museum. The intern will become well-versed in use of the Past Perfect curatorial database program used by all military and Federal museums. At the end of the internship the successful candidate will be well-grounded in the curatorial, exhibit, operational and education components of museum operation. The museum is open to additional requirements that may be required by faculty for intern to receive course credit.

Requirements

The applicant should be pursuing a career in the museum, history, education or military fields. A specialization, knowledge or interest in United States military history is preferred but not required. Applicant should feel comfortable interacting with the public and providing tours for secondary age school children. Applicant must feel comfortable working for the United States Armed Forces and around military personal and should comport themselves accordingly.

Minimum Work Requirement

15 hours per week, to include two to four Saturdays from 9:30 a.m. until 4:30 p.m. each month. Weekday schedule may involve full days or half days.

Stipend

The Texas Military Forces Historical Foundation will pay a stipend of $435 to the selected candidate at the end of each month of completed work.

Working environment

The Texas Military Forces Museum is located on Camp Mabry at the intersection of 35th St. and MoPac. There is no bus access to the museum and private transportation will be required. Intern must have a valid photo ID, such as a driver’s license to enter Camp Mabry. The museum has wifi internet access and interns are allowed to bring a laptop to work.

Apply

Send a copy of your resume and letter of interest to [email protected] Call 512-782-5394 with any questions. Deadline is January 9, 2023 with a start date January 17, 2023 and an end date of May 15, 2023.

Thanksgiving Hours

Memorial Day

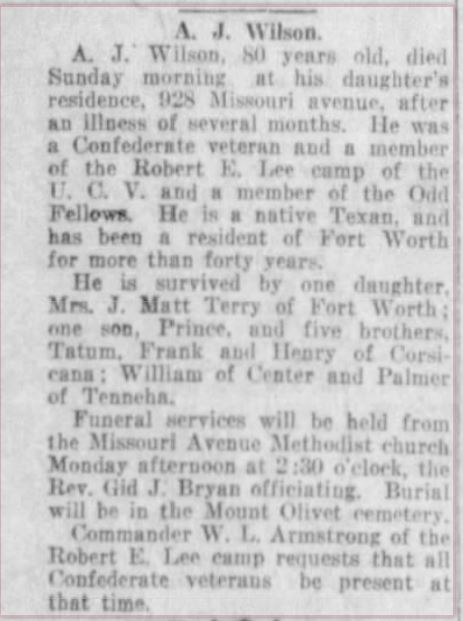

A Civil War Collection and Sock Love Story

We recently discovered a small collection of Civil War items which were donated sometime prior to the professional staff being hired in 2007-2008.

The collection consists of an 1862 letter written by F.E. Ftizpatrick to his sister Eliza. Francis Fitzpatrick was with Company F of the 57th Georgia Regiment. He was captured at Vicksburg, paroled and died at home in August 1863, he was one of 10 children.

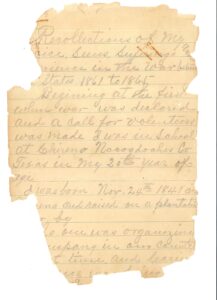

The collection also contained a single, damaged notebook page titled: “Recollections of My Service, Sufferings, and Experiences in the War Between the States, 1861-1865” There was no name associated with the page, but since this person made it to the end of the war it could not be Fitzpatrick and the handwriting looked nothing like his.

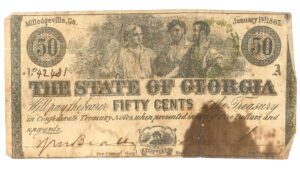

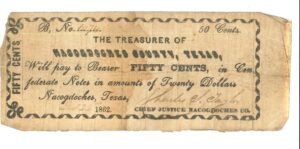

Next were three Confederate bank notes, one from Georgia and two from Texas.

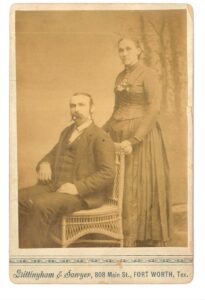

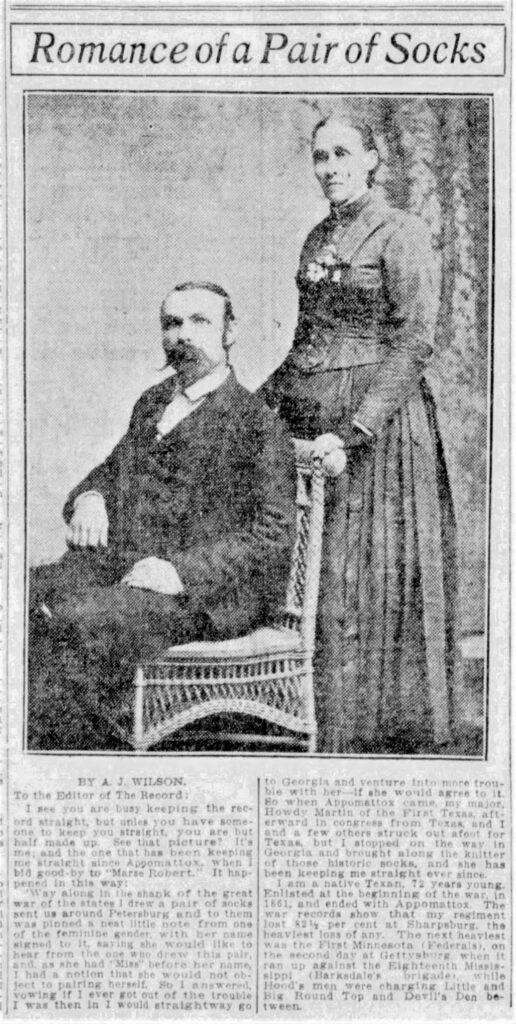

Lastly there was a cabinet card with an image of a couple and a name written on the back: A.J. Wilson and an address in Fort Worth, Texas.

This cabinet card and notebook page were the key to unlocking the mystery. Speculating that they might be related, we checked the name A.J. Wilson with the date of birth and place of enlistment noted on the damaged notebook page. We were able to find an Alfred Jenkins Wilson who served with Company K, 1st Texas Infantry, Hood’s Brigade. Then searching for Alfred Jenkins Wilson we were surprised to find this newspaper article with a copy of our cabinet card!

It provided more of the story including how he meet his wife, shown next to him in the photograph. Her name was Emily Fitzpatrick, sister to F.E. Fitzpatrick! Eliza was here older sister, and Emily was only 2 years older that Francis so closest to him in age of all the siblings. So that provided the connection to the letter, and explained the presence of GA and TX Confederate bank notes

The story of how he meet his wife is told in the newspaper article. She knitted pairs of socks to be sent to Confederate soldiers in need. She pinned a note to the socks asked that whomever received them send her a note to let her know they were being used and included her address. Wilson began to correspond with her and told her if he lived through the war he would come and find her. After the surrender at Appomattox, Wilson traveled to GA, he had relatives who lived nearby and found Emily Fitzgerald, married her and took her back to Texas. Emily dies in 1920 and Alfred in 1921 a love story till the end.

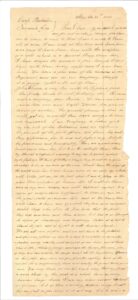

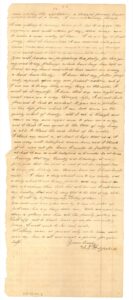

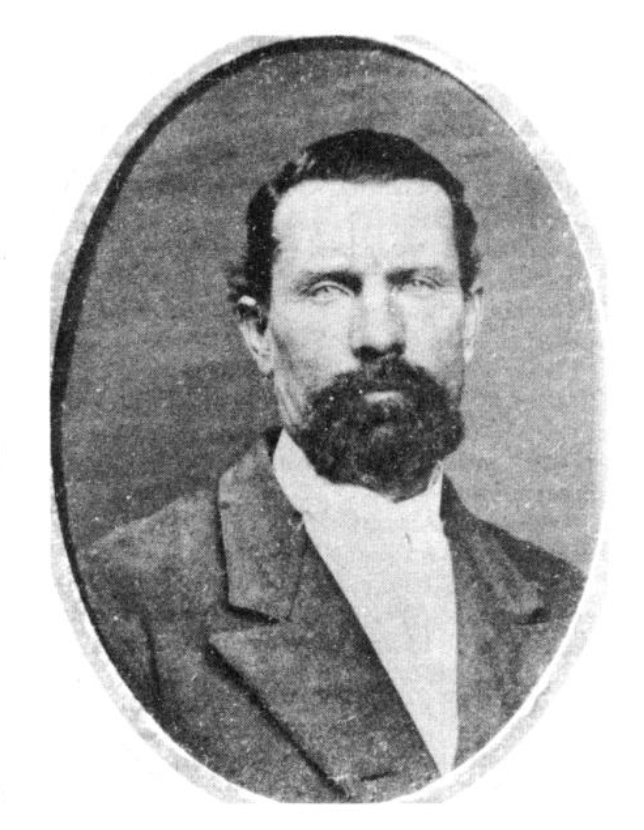

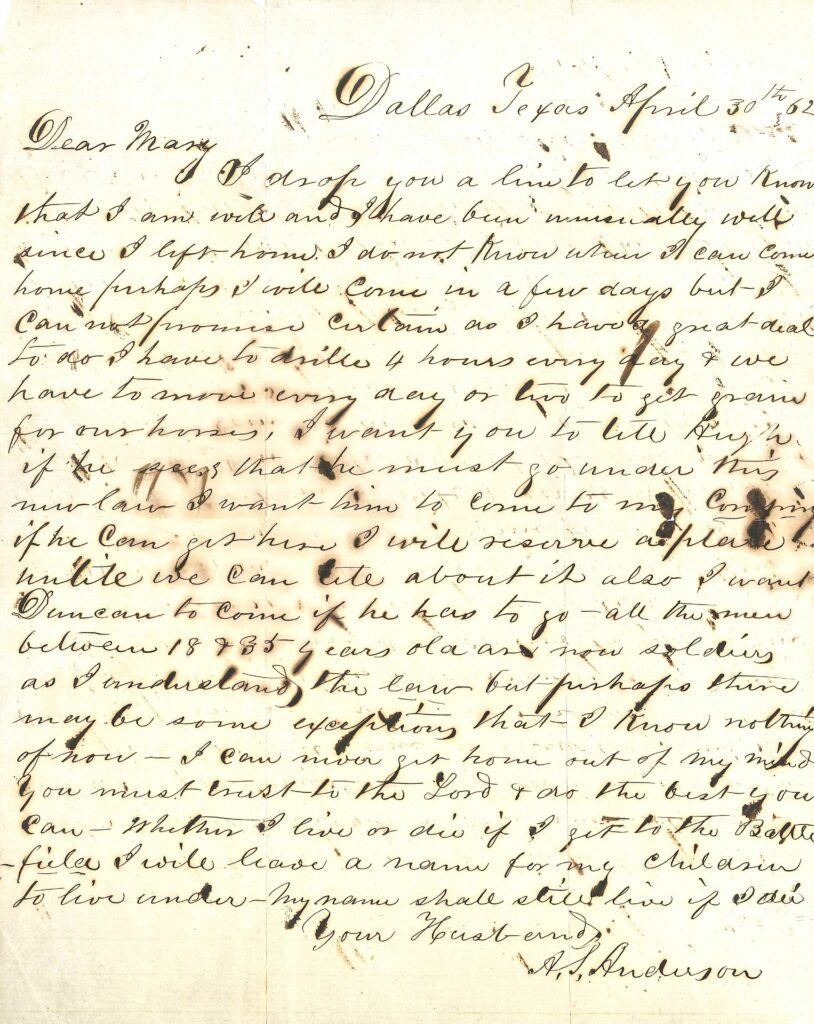

Captain Allen S Anderson Letters

We recently received a donation of four letters written by Captain Allen S. Anderson who served with the 31st Texas Cavalry, Confederate States of America in 1862. Transcriptions of al 4 letters are available here: https://texasmilitaryforcesmuseum.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/09/Anderson-letter-transcriptions.pdf

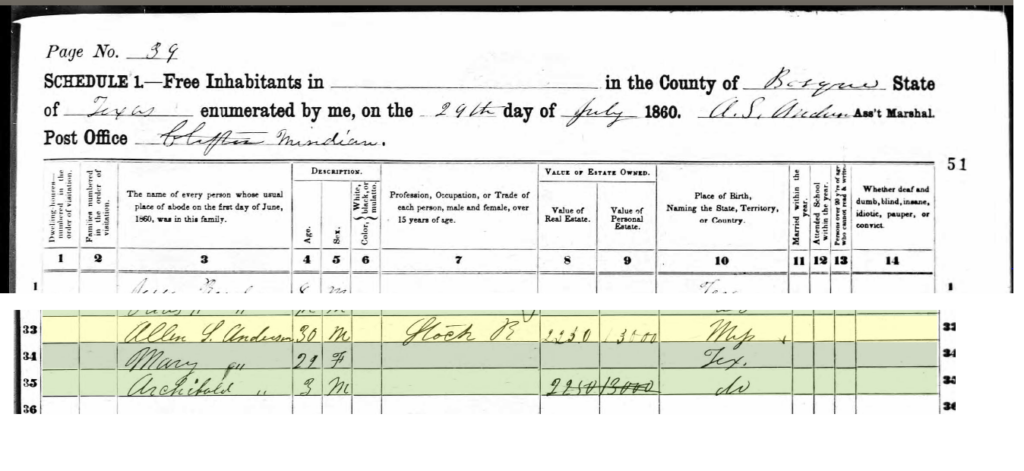

Allen Anderson was born in Florida in 1830, moved to Mississippi, then arrived in Texas in the 1856 where he set up in Bosque County. He was married to Mary Robinson in September 1856. In 1860, He, Mary and their son Archibald were living in Bosque county were Anderson was a Stock Rancher and the Assistant Marshal:

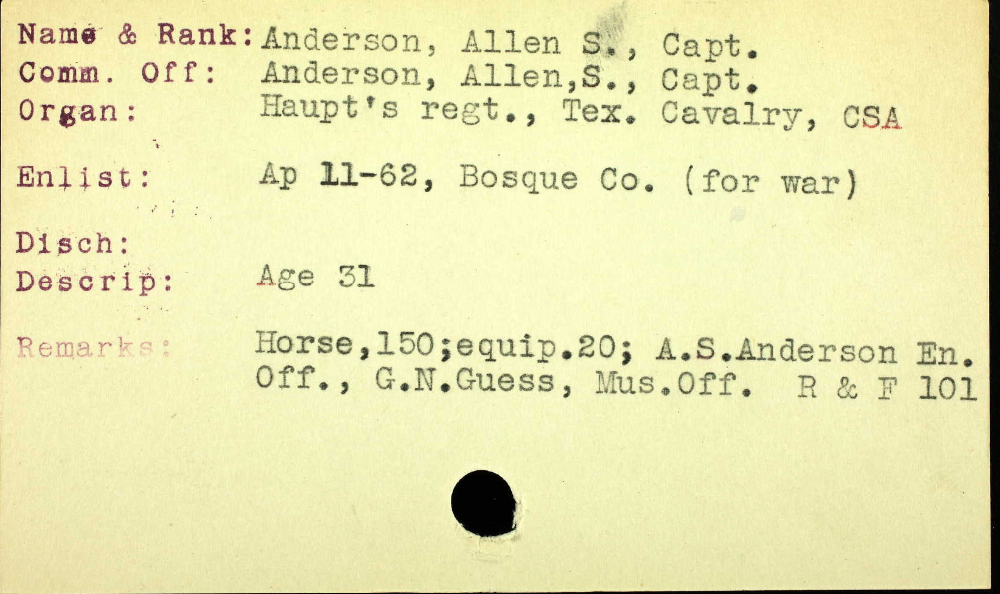

In April 1862, Allen joined Hawpe’s Regiment of Texas Cavalry and was put in charge of Company B, 31st Texas Cavalry.

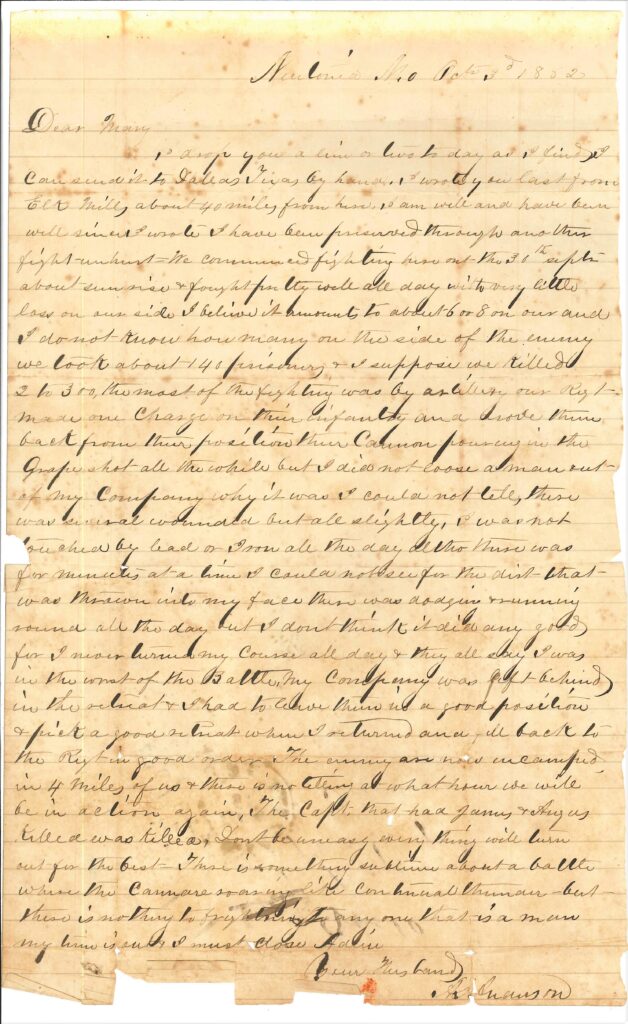

Between April and November 1862 Captain Anderson wrote letters to his wife Mary, four of which were donated to the museum: April 30, 1862, June 25, 1862, September 18, 1862 and October 3, 1862. Transcriptions for all 4 letters can be found at the top of the page. In the letters he speaks of camp life, their mutual friends, discipline in his company, and the battle of Newtonia, MO. The letters are well written and full of descriptive details. His unit, the 31st Texas Cavalry, fought skirmish’s in Arkansas, and Missouri in the spring and fall of 1862. Anderson was wounded by gunfire near Fort Smith Arkansas, and requested a discharge on November 20, 1862 which was granted by President Jefferson Davis on December 24, 1862. Captain Allen S. Anderson returned to Texas and fought as part of the Frontier Protective Unit.

After his return to Texas Captain Anderson’s life took an unexpected turn in June 1864. There are a couple of different versions of what happened. This one comes from the book ” Comanche Indian Fights on the Texas Frontier” by E.L.Deaton published in 1895 it says…In the summer of 1864 Indians came in and stole a lot of horses. The group followed for a day and gave up then the next day as they approached Blanket Creek they saw a horse that had a halter and was sweaty where a blanket had been. Captain Anderson said he saw an Indian go into the thicket E.L.Deaton, Captain Anderson and Aaron Cunningham charged at full speed because they had the best horses. Anderson was in the lead and charged into the thicket. Captain Anderson said he saw an Indian go into the thicket. John Cox cocked his gun thinking Allen was an Indian. Captain Cunningham asked Cox if he saw an Indian and Cox said yes. Cunningham said shoot quick. Cox shot at the hulk. Anderson yelled once, ran out of the thicket and fell into Bill Kingsberry’s arms. He said take my gun and kill him. Cox loaded his gun, came round and saw Anderson was dead. Cox said “My God boys, is it possible that I killed my friend?” He was overcome with grief and wept bitterly. He seemed almost paralyzed. It was an honest mistake but the thought of killing his friend was more than he could bear. Those present at the killing of Captain Anderson were: F.M.Collier, Capt.Jas.Cunningham, Aaron Cunningham, Wally Cox, Tom Deaton, Tom Corn, John Cox, Bill Kingsberry and E.L.Deaton and one or two others he forgot. Another slightly longer version can be found in “The Quirt and the Spur” by Edgar Rye.

Allen Anderson’s body was returned to Bosque County and buried in what is now the Oswald Cemetery in Clifton, Texas. Although his family is said to have moved the body at some point. “Captain Anderson’s wife and two children stayed in Bosque county, where his son, Archibald D., was elected sheriff. Flora, the daughter of Captain Anderson married Joseph A. Kemp, a successful merchant of Wichita Falls, Texas. Both of the families of Archibald D. Anderson and Joseph A. Kemp settled in Wichita Falls and became prominent in the development of that flourishing little city. The wife of Captain Anderson died at Clifton, Texas.” ( From The Quirt and the Spur)

Roswell K. Doughty WWII Memoirs

Major Doughty served with the 36th Infantry Division from 1942 through 1945. His memoirs provide an unique perspective into the command structure of the 36th Infantry Division and the lives of its soldiers. This document was made available by the generosity of his granddaughter and the Doughty family.

Welcome Reader

Welcome, we are pleased you are reading this great historical perspective of Roswell K

Doughty. His unique perspective brings a myopic view of life as an intelligence officer on

the front lines in WW2. Enjoy as you will. I have included a link to the hardcover and Kindle

version of the book for those who wish a more permanent copy.

Laura Landsiedel Ford, granddaughter (my mother was Martha Doughty).

https://www.amazon.com/Invading-Hitlers-Europe-Salerno-Intelligence-ebook/dp/B08VNH8R1Q/ref=tmm_kin_swatch_0?_encoding=UTF8&qid=1622652290&sr=8-1

VIRTUAL TOURS

The museum has begun to add virtual tours to our website. Visit the page here: